Work of the archive

Inesa BrašiškėIn this text I will deliver some provisional notes on the artistic and curatorial engagments with the archive as a material repository of words, images, and stuff. The subject has been with us since at least early 2000s when contemporary artists internationally started engaging with the archival material in a more pronounced manner, as well as curators and writers started reflecting on this widely embraced direction of artistic production. Most recently, Sara Callahan’s monograph “Art + Archive: Understanding the archival turn in contemporary art” (2022) presented a sort of summary or a snthesis of this widespread artistic and critical engagment with the subject. Notwithstanding its global reach, and because of the historical specificities imbricated in the material artists and thinkers usually rely on, I believe that the positionality is still relevant, and the interrogation of specific areas in this respect are still rather scarce.

I will be speaking from and on the Baltic States, and my cases will stem primarily from Lithuania and Latvia and will span from contemporary times to art produced under the socialist regimes. In the art historical scholarship on the former Eastern Europe, the subject of the archive has been so far largely approached from the institutional perspective. The artistic self-archiving in Eastern Bloc was an outcome of the lack of institutional support under communist rule. Artists thus engaged with the archive as a way to remember. In my thinking about the archive as a problem, I am less concerned with filling historiograohic holes than with acknowledig the emancipatory optential of the archive, or what in my title I call “work of the archive.” I must admit that recent decolonial and feminist scholarship in and on the former Eastern Europe is largely responsible for my I own motivation and indeed ignited urgency I feel to speak about the work of the archive in my home. So in the end the motivating question for me is not how the archival openings in contemporary art and curatorial efforts write down the interrupted histories but how these activities create what feminist scholar Karolina Majewska Gude has called provisional narratives for the future. A turn toward the archive is not a turn toward the past, as Kate Eichhorn puts it, but rather an essential way of understanding and imagining other ways to live in the present.

The text will be roughly divided into two parts: first, I take as my case study the work of Lithuanian contemporary artist Aurelija Maknytė (b. 1969). The qualities of her work in my view invite to grasp certain openings in the archive, these are primarily of epistemological nature. First, I take a look at her inwuiry into the agency of the minor figure, of the banal, and of the accidental, and then I point to a place of embodiment and affect in the archival knowledge production. I want to suggest that these openings illuminate the stakes of the recent curatorial practices of interwar and postwar art in Lithuania and Latvia which is the subject of the final part of my text.

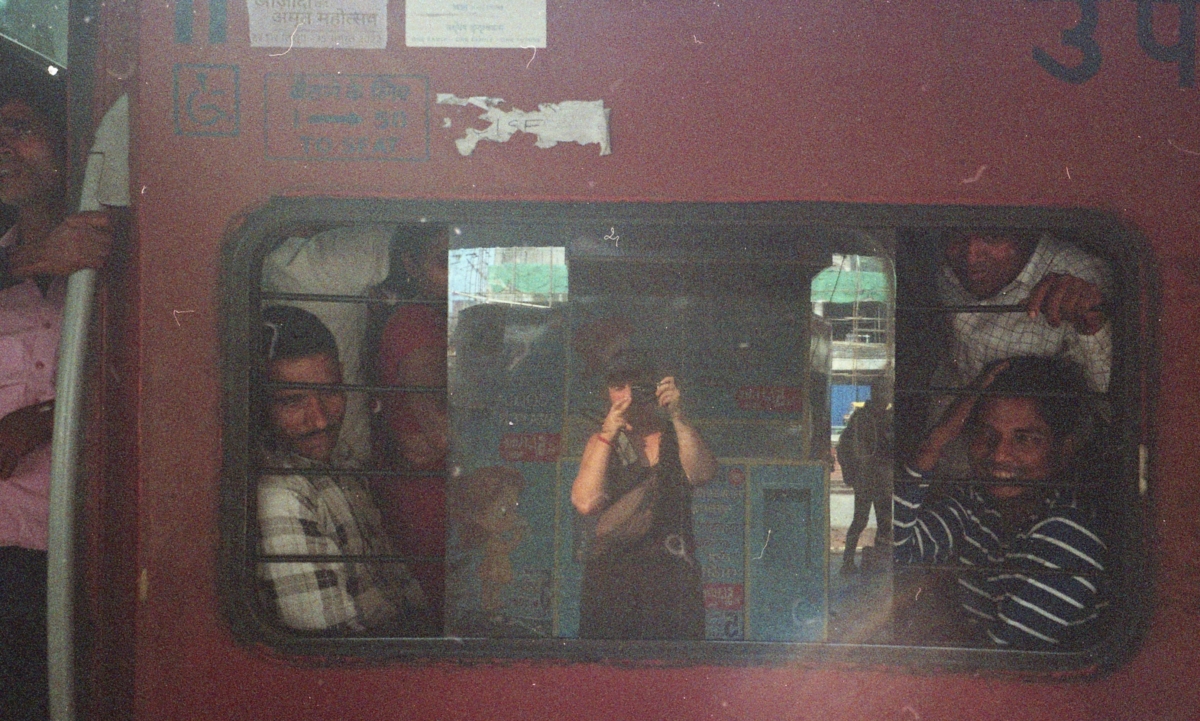

Aurelija Maknyte is a Lithuanian artist who treats family archives, found anonymous material, and television archive, as both information repository and a framing device. Maknyte is a scavenger, an amasser of the weirdest stuff and in great quantiities – oh you must see whats going on in her apartment! – a colleague dropped me a note recently. A biologist turned artist, Maknyte not only actively looks for the documents and found objects (which she gathers in various places from flea markets to abandoned gas stations) but also creates taxonomies out of all this stuff, multiple collections run at the same time. In Invisible Camera (ongoing), for instance, one witnesses her collection of video recordings made by anonymous people who accidentally press the camera’s record button when they intended to stop teh recording. The tapes capture what the person holding the camera sees and hears minutes later captured by the camera not influenced by any compositional or plot decisions. These are literally digital trash. However, in/because Maknyte’s initiated accumulation of this trash, one starts noticing something more: a digital glitch not only illuminates the presence of the recording device as a material apparatus with particular qualities, but also makes a body holding a camera more present than ever.

The bodies in her work are more or less anonymous. In her installation Parents Room, for example, she exhibited a group of found letters written by a mother to her daughter form 1965 to1990. The artist has purchased a whole collection of these letters and presented them typed on an A4 sheets of paper with names of persons and places as well as some details changed so that specific situations could not be identified. Whereas East Central European artists-as-historians tend to operate on the monumental scale (major events, key personalities in the work of another Lithuanian artist Deimantas Narkevicius, for example), Maknyte is always concerned with the anonymous, with the fringes. Her stories are fragmentary, non spectacular, and banal. As she herself admits, “I am certain it is through these the private stories of non spectacualr in that we really get to know the period in all its violence.”

Sutured with emotions, desires, hopes, plays, accidents, horrors and desperations, fragmentary as they are, hers are stories of a minor figures impregnated with time.

In his essay “The Way of the Shovel: On the Archaoelogical Imaginary in Art”, Dieter Roelstraete noticed that post-communist Eastern Europe became a fertile ground of excavation for many artist both from East and West. Maknyte too is invested in the material sediments of history. In one of her installationsshe exhibited the templates for making clothes cut from the Soviet newspaper Tiesa (The Truth) that she found during one of her trips to flea market. The templates manifest their original purpose – a promise of a garment produced by an unknown tailor. In Maknyte’s presentation it turns into a cloth of history itself palpable to the extent it threatens to caress the skin of its wearer. “Both, art and archeology, writes Roelstraete, are also work that remind us of our bodily involvement in the world.”

But this inclination towards the material archaeology of the past is far from fetishistic in Maknyte’s work as her materialism is not concerned with conservation or nostalgia. Hers is the story of doubt: firgetting, obsolescence and dissapearance are always counted in.

In “Art History according to my Father” she arranges a sequence of 80 slides on a carrousel, that her father, an engineer, used to buy during the Soviet times. The slides we see are discoloured from the repetitive use and poor quality of pigments used when manifacturing the slides. Time continues to swallow up the colours of the personal art history and the moment when there will be no image is not hard to imagine.

Maknyte’s work, I suggest, explores not so much what Hall Foster calls “a will to connect” (and here he means, artists connecting disparate elements), but a will to contact, that is to set in motion an affective potential of the living past.

A will to contact with and within the archives is presicely what we witness in the curatorial activities in recent years in the Baltics. In the last part of my talk I will consider the legacy of a Lithuanian photographer Veronika Šleivytė (1906–1998) and Latvian photographer Zenta Dzividzinska (1944-2011) who each on her own right and in her own time accumulated vast collections of images against the grain, manifesting concern with the marginal, the quotidian, and the intimate. The autobiographical photographic corpus makes up an important but untill recently invisible portion in each of their elusive archives.

Vast archival holdings of Dzividzinska’s work contains hundreds of negatives and prints, contact sheets and documents mostly concerned with the daily life of three generations of women in the Latvian countryside, and ignored during her lifetime. In 2021, KIM? Project space in Riga has organized an exhibition of Dzividzinska’s archive for which they invited an Austrian contemporary artist Sophie Thun to engage with the legacy of Dzividzinska’s art practice. Thun errected a photo lab and an archivist’s workstation in the gallery space and during the run of exhibition engaged in various activities from developing Dzividzinska’s negatives to making her own indepednent work. The photograms featuring Thun’s hands interacting with photographs of Dzividzinska captures this particular – embodied – engagement with the para-feminist archive making the latter a vibrant place to think with and to care for in the present and for the future.

I want to end my text with this slide. It shows a participant of the Kaunas Pride holding a book. The latter is the first major catalogue of Veronika Sleivyte, Lithuanian artist and photographer. A few years ago, the never seen photographic works of hers were uncovered in her personal archive in one of the regional museums by a curious art historian and curator. This particualr corpus of her images from the first half of the XXth century are mostly artist’s self portraist and staged photoshoots, some of these images are arranged in the diary like sequences. This part of the archive tells the stories of Sleivyte’s private life, of lesbian love and care, separations and longing. Once private imagery was soon made public in exhibitions and accompanying catalogue. It is still a history, but now this history has become an agent acting with and for a queer community in todays Lithuania. The archive, in other words, started to work.

Naujas etapas: įsteigta Lietuvos fotografijos meno draugija

Naujas etapas: įsteigta Lietuvos fotografijos meno draugija

„Jaunojo dizainerio prizas 2025“: konkurso nugalėtojus rinks tarptautiniai dizaino ekspertai

„Jaunojo dizainerio prizas 2025“: konkurso nugalėtojus rinks tarptautiniai dizaino ekspertai

Institucijos(e) yra žmonės. Pokalbis su Rupert rezidencijų ir viešųjų programų kuratoriumi JL MURTAUGH

Institucijos(e) yra žmonės. Pokalbis su Rupert rezidencijų ir viešųjų programų kuratoriumi JL MURTAUGH

Art Deco muziejaus įkūrėjai apsilankė Ludolfo Liberto parodoje: jis galėjo įkvėpti Lietuvos žmones drąsai

Art Deco muziejaus įkūrėjai apsilankė Ludolfo Liberto parodoje: jis galėjo įkvėpti Lietuvos žmones drąsai

Kaune – unikali mokymų programa jauniems kūrėjams

Kaune – unikali mokymų programa jauniems kūrėjams

MO videožaidimų parodos kuratorė rekomenduoja: penki žaidimai lietingai vasarai

MO videožaidimų parodos kuratorė rekomenduoja: penki žaidimai lietingai vasarai

Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus kitais metais atidarys parodą Nagojoje

Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus kitais metais atidarys parodą Nagojoje

VDA Telšių galerija kviečia kuratorius, menininkus, tyrėjus bei kitų kūrybinių veiklų atstovus teikti paraiškas 2026 m. parodų (projektų) rengimui

VDA Telšių galerija kviečia kuratorius, menininkus, tyrėjus bei kitų kūrybinių veiklų atstovus teikti paraiškas 2026 m. parodų (projektų) rengimui

Monika Pietarytė Klaesson: „Kviečiu stabtelėti ir sąmoningai pažinti fotografijos meną“

Monika Pietarytė Klaesson: „Kviečiu stabtelėti ir sąmoningai pažinti fotografijos meną“

Antanas Sutkus su bendraminčiais inicijuoja Lietuvos fotografijos meno draugijos įkūrimą

Antanas Sutkus su bendraminčiais inicijuoja Lietuvos fotografijos meno draugijos įkūrimą

Ukrainiečių jaunimas pristatė trumpametražių filmų instaliaciją „Kauno dienoraščiai“

Ukrainiečių jaunimas pristatė trumpametražių filmų instaliaciją „Kauno dienoraščiai“

Nemokami renginiai Bėgių parko angare: prasidėjo festivalis „Gilios upės tyliai plaukia 2025“

Nemokami renginiai Bėgių parko angare: prasidėjo festivalis „Gilios upės tyliai plaukia 2025“